“Everything that takes place on the screen — a Mutant attack, a powerpack munch, an asteroid cluster, plus noises, colour, maneuvering — is simply the machine’s response to information”.

– Amis, Invasion of the Space Invaders, pg. 112

In 1982 director Steven Spielberg diagnosed enfant terrible Martin Amis with “…a terminal case of video addiction”. This outlandish statement greets the reader at the beginning of Invasion of the Space Invaders: An Addict’s Guide to Battle Tactics, Best Scores and the Best Machines (1982) Amis’ book on arcade games and early video game culture. At first glance, Invasion of the Space Invaders stands apart from Amis’ oeuvre. It covers an unserious topic, games. Even forty-one years ago, video games were culturally significant enough to attract the attention of both a revered child of the literary world like Amis (the son of renowned British writer Kingsley Amis), and Spielberg who wrote the book’s short introduction.

The subtitle of the book promises An Addict’s Guide to Battle Tactics, Best Scores and the Best Machines, however, ultimately, it’s a collection of musings about the potential impact that video games might have on our future as seen by Amis back in 1982. Amis’ experiences playing in arcades across France, New York City, and England inform the words found in this book. Although, in Invasion of the Space Invaders he mainly stresses the negative and pays little consideration to any potentially positive value video games might have for our wider human society.

What follows is Aguas’ Points look at this odd book written by Amis who passed away on May 19, 2023.

Player = Addict: The Video Invasion Came from Capitalism Not Outer Space

From the start Invasion of the Space Invaders tackles the topics of video game addiction or infatuation. Amis goes to some length to describe his “addiction” to arcade games. Amis reflects on “Space Invaders, my first love” the game that “ravished, transfigured, swept away… invaded” his life. On the same page, he describes how addiction is “programmed into the computer”, so maybe his love for the game wasn’t genuine but more of a fixation engineered by the tech wizards at Taito. In that case, our poor British chap didn’t stand a chance.

According to Amis, players get more than just gameplay from playing games. The “video game tells a story” Amis states, but to get the story requires a steady stream of coins. Oh, the dilemma! Amis continues with the key insight that games can be “theoretically infinite”, so if one is skilled enough or has a bottomless pocket full of coins one can play for as long as one is able. So, logically the rich or addict will play for longer, while the poor might only get a few tries.

Amis attempts to attribute the appeal of arcade games to addiction, exhibited by players eager to drop copious amounts of coins to play more. Paying the price is an essential part of the experience of arcade gaming, but how much of players’ eagerness to spend money is simply linked to the novelty of arcade games in the late 1970s and early 1980s? So many questions are raised by this book.

How does one get “Pac-Man Finger”, a malady that afflicted an actress obsessed with Pac-Man acquainted with Amis? How many hours did she spend in front of those machines moving the joystick so that eventually her index finger looked like “a piece of liver”? How many wakka wakkas did she hear? Was Amis really addicted? For the sake of sanity, I’ll take him at face value. But it’s hard to believe him due to him being so flippant, gaudy, bad-mannered, and such an Amis throughout Invasion of the Space Invaders.

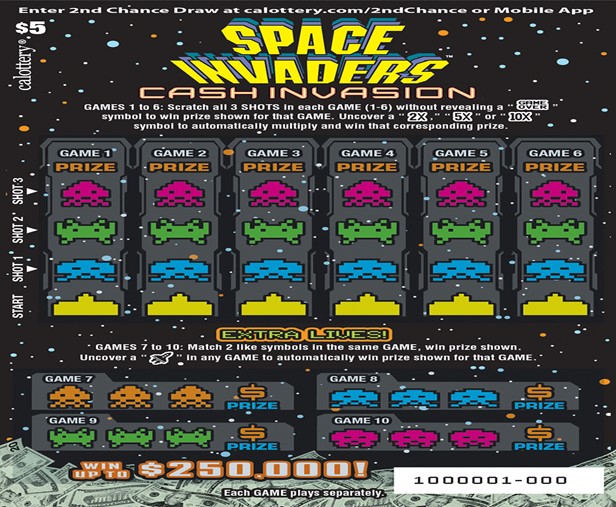

(Source: calottery.com/scratchers/$5/space-invaders)

Invasion of the Space Invaders has a transparent fixation with the unsavory aspects of early arcade culture as Amis saw it. Arcades from Amis’ experience were frequented by pedophiles, teenage “faggots” and addicts. They were dens for ramped consumption akin to gambling and had the stench of hell. Amis sure knew how to pick where to hang out. The relationship between criminal activity and arcades is a natural one here. There is even a moment in the book where Amis details how kids resort to crimes, specifically theft, and even prostitution, in order to get the money needed to play. Yet, Amis continues to play in these dingy places. Potentially there is a critique and insight into our current moment in capitalism, where choosing to engage in leisure over work is self-effacing, if not criminal. After all, absurdity would become a hallmark in Amis’ work where satire and caricature are how humans are presented in a world thrown off kilter by greed and ubiquitous consumption.

Don’t Bother Defending the Front: The Aliens Are Here to Stay

“The average arcade-foddder homo may not be very sapiens but, my is he ludens. And games have simply never been as good as this before. One way or another they burrow deep into the brain”.

– Amis, Invasion of the Space Invaders, Pg. 29

In 2018, Simon Parkin’s review of Invasion of the Space Invaders for The Guardian made the bold claim that this book was “how games criticism was born”. Surely this is a ridiculous pronouncement that makes no attempts at engaging with writing on games already in existence in Japan and other places before 1982 (more on this later). One thing is clear though, Invasion of the Space Invaders is authored by arguably the most respected and famous writer to have written about video games in the West in 1982.

Invasion of the Space Invaders was meant to capture the craze of arcade games in a novelty book. Maybe Amis wrote it because he needed the money or maybe he really was obsessed with video games. Regardless of the intent, many aspects of the book have not aged well. The odd representation choices seen in the book’s photographs and Amis’ punchy language will leave many readers feeling uncomfortable. Yet, to Amis’ credit, Invasion of the Space Invaders is a well-written affair. Today, many of the best books on video games are academic in tone and content or are histories aimed at informing readers through the retelling of pivotal information about the development process of a game or major shifts in the wider culture of games. Invasion of the Space Invaders is neither of these. It’s an odd mix of memoir, strategy guide (the dominant type of book on games at the time), and consumer-driven review compendium, as well as cultural criticism. The mélange works.

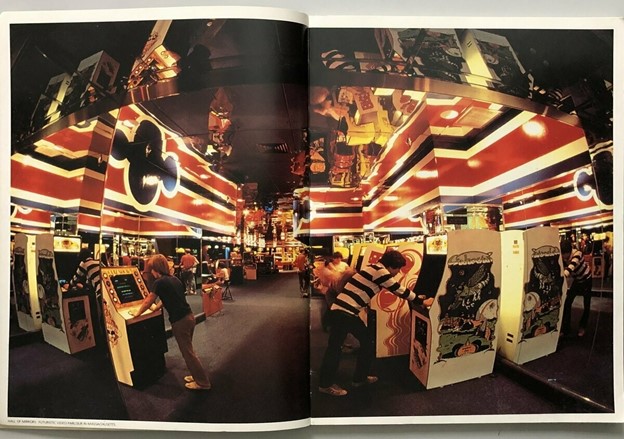

One highlight of Invasion of the Space Invaders is its photographs. They are time capsules. The photos of people gathered around old arcade machines both playing and spectating show that games are social and performative. This communal aspect of the arcade is only alluded to by Amis due to his lack of enjoyment with playing with other people. In his words “Homo Ludens is ultimately competing against himself”. Instead of community and cooperation, there is an emphasis on competition. Yet, Amis does make a point in highlighting the figurative playground of video games as a space where youngsters are well adept to strive while older players, Amis included, can only hope to play well.

Amis is ahead of the curve in his appreciation of games as performance. For example, refers to players of Missile Command as “half bongo-player, half concert pianist”. He marvels that he can do is “watch, and wonder at, those inscrutable geniuses”. On a quick side note, it’s quite amusing to find Amis taking the time to breakdown the initials left behind by other players in high score screen.

Throughout Invasion of the Space Invaders, Amis makes use of horrid details and scary tales to captivate the reader. There are more stories in the vein of “Pac-Man Finger” within the book. These stories are not dissimilar to the sensational reports made at the time on the evils of arcade games. With his irreverent humor, Amis derides a British politician who argues in support of arcade games by stating that players might have a difficult time having any spare money for drugs after spending it playing Space Invaders. Amis refutes, “Yes, but the same could be said if the money was spent on hand-grenades or ringside seats at bear-baiting bouts”. Amis is flippant on any potential positive effects that could be attributed to video games.

He deliberates that the main reason games are made is a “question of money”. This reductive remark, though essentially true, offers little in the way of insight and buries the work and thought of those the designed and created arcade games like Pac-Man or Defender. There is more vitriol to be found in Invasion of the Space Invaders like the statement that video games grew out of a “moronic rod”. No surprise then to see Amis align video games with pornography. He ends up dismissing them as “selfish and pointless gratification”. To top it all off, the book is riddled with racists and stereotypical characterizations. Japan and the Japanese are the main targets of words linking their games to an invasion. They are also both techno genius and “sardines”. There is even an allusion to the Japanese and their arcade machines as “little green men”. Naturally, we can only be invaded by others, so Amis those his best in creating the others.

As far as criticism of specific games, Amis sees Frogger and Donkey Kong as examples of “boring games” that “will not last”. Though he is wrong about the lasting power of these games he still sees, in an offhanded way, value in Donkey Kong and states that “it is more fun to speculate what Nintendo will bring us in the future”. Most of this could be found in Part II of Invasion of the Space Invaders which is both a walkthrough/tips section and review/criticism of various games. Here Amis praises space games (video games set in space) as “wonderful games”. And elaborates by stating his appreciation for Asteroids, and Space Invaders and considers Defender “perhaps the most thrilling” game.

Below is a list of most of the games reviewed in this part of the book by Amis:

Space Invaders – Galaxian – Asteroids – Pac-Man –Defender – Scramble – Cosmic Alien – Lunar Lander –Battlezone – Missile Command – Gorf – Pleiads – Frogger – Centipede – Donkey Kong – Turbo – Video Hustler – Pro-Golf – Dribbling

***

In terms of tone and language, Invasion of the Space Invaders is a progenitor to what will be found in Game Players magazine, and the work of the verbose Tim Rogers. There is a major distinction though, Amis seems to have a chip on his shoulder. He derides games and those that make and play them. From Amis’ perspective, why should he be positive about video games when they are just a waste of time? To that one can ask, well why spend time writing a book on video games?

(Source: Game Players, October 1994 issue, Final Fantasy III review)

Another criticism of the book is Amis’ intent. He writes with intention. Meaning that the gendered language found throughout the book is intentional. For example, though there are pictures of women playing games in the book and the individual inflicted with “Pac-Man Finger” is an actress, the ideal player in Amis’ eyes is male. There is little mention of designers and creators of games. This, however, might just be emblematic of how games were covered and credited at the time. The prevailing practice was to give corporations rather than individuals or groups of people credit for creating the game. This was just business.

Beating the Games in Mother Earth

Amis wasn’t alone in writing books on the video game arcade craze in 1982. That year saw the release of Ken Uston’s SCORE! Beating the Top 16 Video Games, Defending the Galaxy: The Complete Handbook of VideoGaming by Michael Rubin, Carl Winefordner, and Sam Welker, The Winners’ Book of Video Games by Craig Kubey, Playing Ms. Pac-man to Win! by Video Games Book, Inc., and Len Albin’s Secrets of the Video Game Super Stars, and Jeff Rovin’s The Complete Guide to Conquering Video Games: How to Win Every Game in the Galaxy. There was a market for these books, but out of all these only Invasion of the Space Invaders can be considered criticism.

The final part of the book is a deep dive into the evolution of video games beyond the arcade as it looked in 1982. It is also a brief examination of early handled games and consoles. These were gadgets that Amis did not like. Only Pacman 2 gets his approval “…the first handled game of any merit”. Though, Amis did consider Nintendo’s Game & Watch, “a range of video toys”, as better in many regards than handles that simply tried to imitate or port existing arcade games. Amis also takes the time to think about the future of video games. He predicts the ubiquity of home console video games later in the 1980s. In his words, “Before long the green monsters will have forced their way into every self-respectingly affluent home”.

Let’s go back to Parkin’s “how games criticism was born”. Invasion of the Space Invaders was not the only place for video game criticism in 1982. For example, Video magazine’s “Arcade Alley” served as one of the first columns on video games. Its columnist Bill Kunkel, Arnie Katz, and Joyce Worley later created Electronic Magazine in 1981, arguably the first magazine dedicated solely to covering video games in English. Another example of earlier video game criticism could be found in 1977 with the birth of Play Meter. It began covering pinball machines but quickly moved to include arcade game machines as well.

In 1982 arcade games were trendy and seen as the future of entertainment. Nevertheless, this was also an unusual topic for a writer of Amis’ renown to write about, let alone write an entire book about. In 2023, forty-one years later, Invasion of the Space Invaders is now a relic, a nostalgia-inducing concoction. It is fitting that the book ends with pages of lines of code as video games are code, the essence of video games. Yet, the talk and mystique around this book are based solely on Amis’ reputation as a writer. Let’s not forget that on Mother Earth others were also writing about games in 1982.

(Source: Invasion of the Space Invaders: An Addict’s Guide to Battle Tactics, Best Scores and the Best Machines)